That sucks. Sod off!

What exactly do you mean?

A non-theatre post

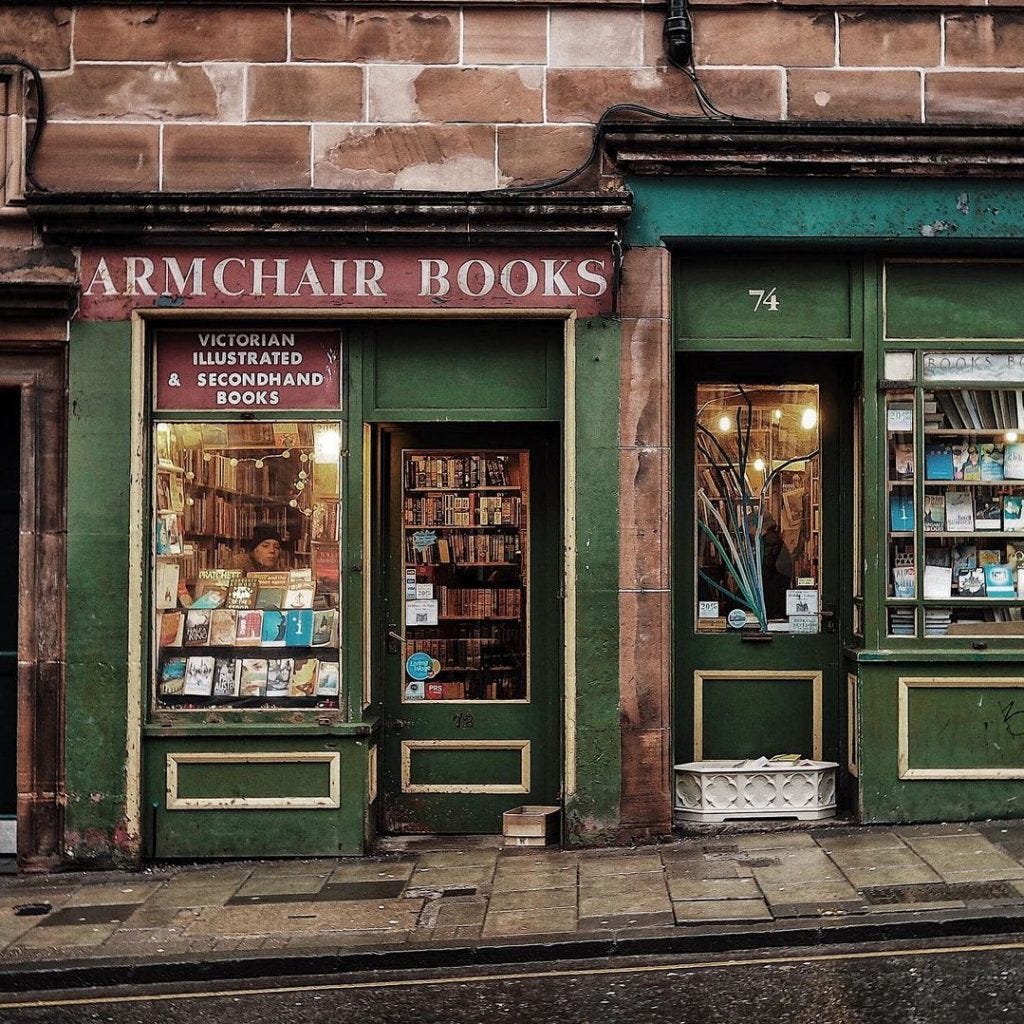

When in Edinburgh I try not to walk up, or down, West Port for fear of being drawn into Armchair Books. It’s a thin, narrow shop with volumes stacked up to the ceiling and always full of browsing students and tourists. Its broad selection - secondhand, of course - tends towards the popular but there are always hidden gems to be found.

The last time I was there I escaped with no more than half-a-dozen titles, which are now stuffed onto my just-bought-must-read-soon shelves. Among them were a couple of Agatha Christies in modern Greek, challenging me to confirm I am as fluent in the language now as I was when I lived in Chalkis decades ago. My priority, however, was John McWhorter’s Nine Nasty W*rds: English in the Gutter Then, Now and Forever, an informative overview of the origins and changing uses of such words as “damn” and “hell” in mediaeval times to the notorious word-which-must-not-be-Named today.

I particularly appreciated his survey of “faggot”, which included all the British meanings - old woman, bundle of sticks, and meatballs - that I grew up with long before the US insult reached these shores. The suggestion that “fag” as in cigarette derived from the bundle of sticks was new to me; I think it feasible although I’m not fully convinced. He also touched on “fag” as a young boy in prestigious British boarding schools who carried out menial tasks for an older boy without discussing the origins of the word. (For better or worse, depending on your perspective, that tradition has died out.) My suspicion is that it comes from “fag”, as in physical-work-making-one-tired - “I was fagged out” is a phrase from my youth which I no longer hear.

There was one linguistic trail that McWhorter did not follow. In the years after the Second World War - although possibly also long before - it was received wisdom among British men who enjoyed sex with men that oral intercourse was the preferred activity in the United States while the anal variety was more popular in the UK. From these pleasures came insults that would only be familiar on one or the other side of the Atlantic - cocksucker and sodomite.

To call someone a cocksucker was, and for many still is, to insult them; from there it is easy to move from “You cocksucker” to “You suck cocks” and easier still to call out “You suck!”. By this point the explicitly sexual reference has disappeared but the idea of disapproval remains. From “You suck” to “It (the situation) sucks” is a logical development and from there to the self-deprecating “I suck”, when the speaker admits incompetence at some activity that almost certainly has nothing to do with sex. So widespread is the expression today that I doubt that the child who pouts “That sucks” has any inkling of the original meaning of the phrase - and I strongly advise against enlightening them.

In Britain, meanwhile, the trail led from “sodomite” to “sod”, as in “You sod!” directed at someone who has done something the speaker dislikes. From the cognate “sodomise”, we get “sod off”, an expression that echoes but is less harsh than the aggressive “fuck off”. The sexual connotation remains but in both exhortations the actual message is “go away / leave me alone”. Now that a classical education is enjoyed by - or inflicted on - very few Brits, like the child ignorant of the backstory to “sucks”, will be aware of its origins. Meanwhile, although “sucks” appears to have become an essential element of many people’s idiolect (look it up), “sod” is heard less and less frequently.

Back to the title: “That sucks. Sod off!”. The combination jars. Some young Brits may say “That sucks” but in general the expression is too American for our genteel ears. “Sod off”, meanwhile, baffles most down-to-earth Americans. That mutual incomprehension should not dishearten us, however; there are many other insults in the English language, sexual or otherwise, that we can use in the certainty that they will be universally understood if not always welcomed.

The next post, a few days from now, will return to the theatre: Antonio’s hatred of Shylock in The Merchant of Venice