What do you have in mind?

Owen Wymark and "The Inhabitants"

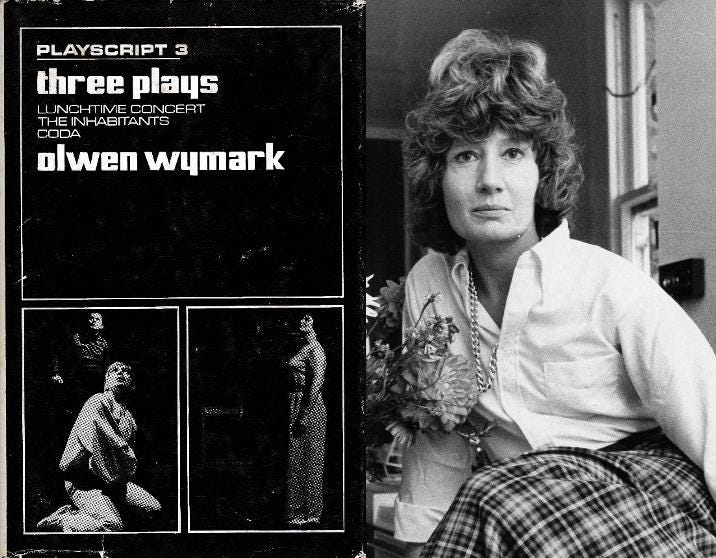

Last Friday the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain announced the winners of its annual Olwen Wymark Theatre Encouragement Awards. WGGB, which straplines itself as the Writers’ Union, initiated the awards in 2005 in honour of the former Chair of the organisation, who died in 2013.

Coincidentally, that day was just over a week after I had invited a group of theatre creatives to read one of her plays. Although she wrote many stage productions and radio dramas, Wymark’s work is seldom perfomed today apart from Find Me, which is is popular with amateur groups. On a trivial note - although perhaps not trivial to her - she was a grand-daughter of writer W W Jacobs (now best remembered for The Monkey’s Paw) and wife of actor Patrick Wymark (né Cheeseman). In a refreshing change from custom, Cheeseman took Wymark as his professional name, having borrowed it from the said William Wymark Jacobs.

The four-hander play that my guests read was The Inhabitants, one of three short plays presented by the Citizens’ Theatre Company in Glasgow at the Close Theatre Club in 1967. Presenting a production in a “club”, theoretically not open to the public, was common for controversial plays before theatre censorship ended in 1968. The Close was a leading avant-garde theatre as well as a gay bar avant la lettre and many famous actors and performers, such as Steven Berkoff and Billy Connolly, appeared there. (Read more here)

Although it was well received at the Close, I can find no evidence that The Inhabitants or the other two plays (Lunchtime Concert and Coda) were ever performed after 1967. The actors, however, all had careers before and / or after the production. Margaret Courtenay (the Woman) had extensive stage and theatre credits before she died in 1996; Bernard Hopkins (the Man) appeared mostly in television and film, as did Arthur Cox (the Boy). There is least information about Robert Docherty (the unseen Voice) online, but it is likely that he was the Bob Docherty who appeared in six episodes of the BBC serial The Eagle of the Ninth in 1977.

The writer, the theatre, the actors . . . what about the play? It’s a typical product of its time, nearing the end of the Theatre of the Absurd. The scene opens with an alarm ringing in darkness, light comes on to reveal Man, Woman and Boy on an almost bare stage, eyes closed, facing up into the darkness as a Voice gradually comes out of sleep. The three ask each other whose turn it is to begin. There follows a series of discussions, false starts and scenarios in which uncertain and fluctuating identities are assumed, with interruptions from the Voice and occasional resets as an unseen tape recorder rewinds and they return to a previous statement or position.

The dominant, but not the only, thread throughout the play is the idea that the Boy is the lover of the Man, which displeases the Woman, who is either the Boy’s mother or his mistress. Among the other scenarios are the execution of the French revolutionary Danton and strange visions that may be dreams. At one point, when the frustrated Voice asks to be given something ordinary from every day life, they offer:

WOMAN A small blind slug in the salad.

MAN A French letter floating in a mud puddle.

BOY An enema.

WOMAN Stepping barefoot on something slimy in the dark.

And so on. You get the picture, or rather the pictures. The play ends with the three stating Thomas Aquinas’ requirements for beauty - wholeness, harmony and radiance, the Voice musing “The mind... the perceptions... God! The satisfactions of thinking!” and darkness falling as the three on stage back in their original positions failing to suppress laughter.

What’s it all about? Your guess is as good as mine. I suspect that our guesses are that the three reflect the internal workings of the Voice’s mind as in Inside Out or The Numskulls. When I first came across the script years ago, an acquaintance suggested Freud’s theory of the Id (the primitive uncontrolled self), Ego (the self-aware self) and Superego (the self bound by the society around us). In that analysis the Boy would be the Id, the Man the Ego and the Woman the Superego but while the Boy has all the unrestrained energy of youth, the distinction between the adult personalities is not clear.

No matter; vagueness allows for experimentation and different interpretations. I had asked for the play to be read to allow me to consider whether I would want to direct it. There are some wonderful moments to bring to life, it would be fun for the cast to create as mood and meaning abruptly change, and there are great opportunities for lighting effects and possibly sound. But we are no longer in the 1960s and although the Theatre of the Absurd still has its devotees, Vladimir and Estragon are still waiting by that tree and La Cantatrice Chauve (The Bald Soprano) continues its sixty-year-plus Parisian run, plotless plays such as A Resounding Tinkle and The Bed-Sitting Room are no longer performed.

So The Inhabitants returns to the shelf where I have dozens of plays waiting to be read and I turn back to the two dramas I am writing and which demand my attention. Before the dramas, however, a dram is calling . . .